By-catch, the Dark Web and the demise of AlphaBay

By: David Roberts, Reader in Biodiversity Conservation, University of Kent & Julio Hernandez-Castro, Senior Lecturer in Computer Security, University of Kent

It seems that every day a new bit of tech comes out or a techy avenue is found that conservationists want to exploit. In relation to the illegal wildlife trade, first it was drones to catch poachers and now it is wildlife trade on the dark web. Tech can work well in the right places, but it does have its limits and conservationists need to understand these. In the case of drones, they are precision instruments so flying them at random rarely detects poachers, but used in conjunction with intelligence to move to specific locations they can be effective.

The Dark Web is an intriguing place, having come to public attention with the rise and fall of the Silk Road trading site and its sister site, the Armory. The Dark Web is the home of illicit trade including drugs, arms and counterfeit items, and there has been much speculation that it is also home to illegal wildlife trade. After one conservationist posted on the Dark Web, requesting to purchase a shark fin, they told me they were amazed to have received a response offering them a quantity. Illegal trades are connected, that is true, therefore it isn’t particularly surprising that they were offered shark fin. If I asked for a Mars Bar on the Dark Web, someone would sell me one, but I’m pretty confident that isn’t Mars’ main sales outlet. That said, Julio Hernandez-Castro and I, along with a number of computing students, have been monitoring trade in wildlife on the Dark Web and it is present, albeit in small quantities (Harrison et al., 2016; Roberts & Hernandez-Castro 2017).

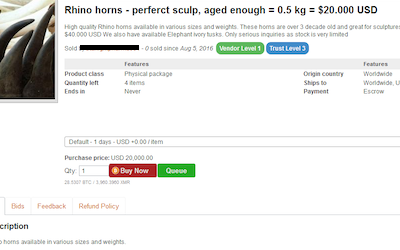

In our recent paper we found that the trade appears to take two forms that can only be described as ‘bycatch’. The first form of ‘bycatch’ was found to be wildlife trade that is also illegal for another reason, notably cacti to make mescaline and reptile leather products. The cacti are primarily illegal because of their narcotic properties, and the reptile leather products are illegal because they are counterfeit designer brand items. As a result, these items are on the Dark Web for reasons other than the fact they are potentially illegally traded wildlife products. The second form of ‘bycatch’ was found to be because the seller is already involved in other illegal activities and therefore probably did not want a surface web presence that could jeopardize their identity. In the very few cases of potentially genuine ivory and rhino horn sales, they were found to be in association with the sale of illegal prescription drugs.

Much of the trade we have found on the Dark Web has been on a marketplace called AlphaBay. Ironically, the month our paper was published, AlphaBay, like the Silk Road, was taken down, shortly followed by another Dark Web marketplace, Hansa market. It will be interesting to see whether these items we previously detected will reappear on another marketplace or if other, new items will appear; certainly as of the beginning of August nothing has appeared. Currently, the most likely marketplace that previous AlphaBay sellers will move to is a site called Dreams that was established in 2013 and therefore has the reputation a seller will seek. However, in reality every day billions of transaction takes place on the surface web; of these, a fraction represent illegal trade in wildlife. This makes detection by law enforcers difficult, particularly as much of the searching is currently done manually. While the Dark Web may be an attractive draw for conservationists to delve into, in reality this platform is likely to be a very minor player, just as the links between the ivory trade and terrorism have been overplayed. While some monitoring is worthwhile in terms of forming a baseline, considerably more effort needs to be focused on the trade over the surface web, particularly trade occurring on closed sites of social media platforms.

Article edited by: Nafeesa Esmail