Solutions for managing shark and ray trade through molecular species identification techniques

By: Andhika Prima Prasetyo, Researcher, Ministry for Marine Affairs and Fisheries, Indonesia; Doctoral student, University of Salford

Located between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, Indonesia is at the epicentre of marine biodiversity, making it a priority area for global conservation efforts. About one-fifth of all Chondrichthyes species (the cartilaginous fish: sharks, rays, skates and chimera) are found in this region, with more species still awaiting discovery.

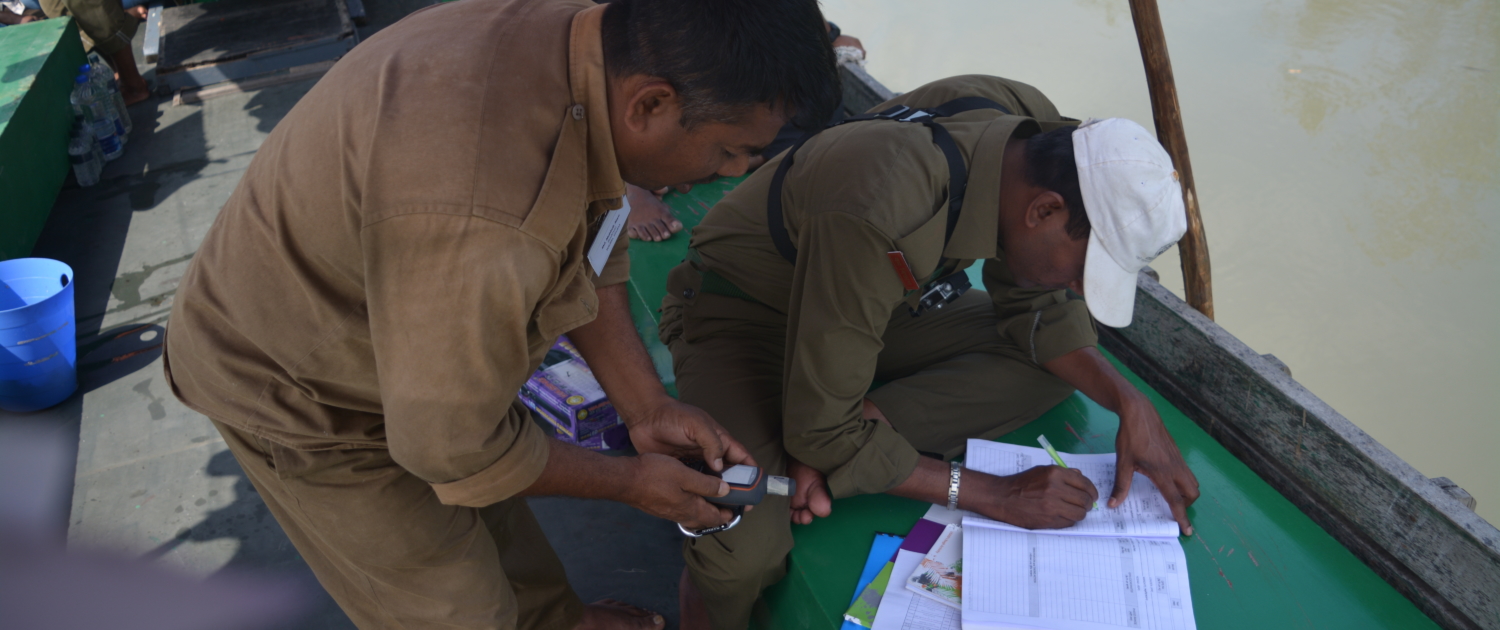

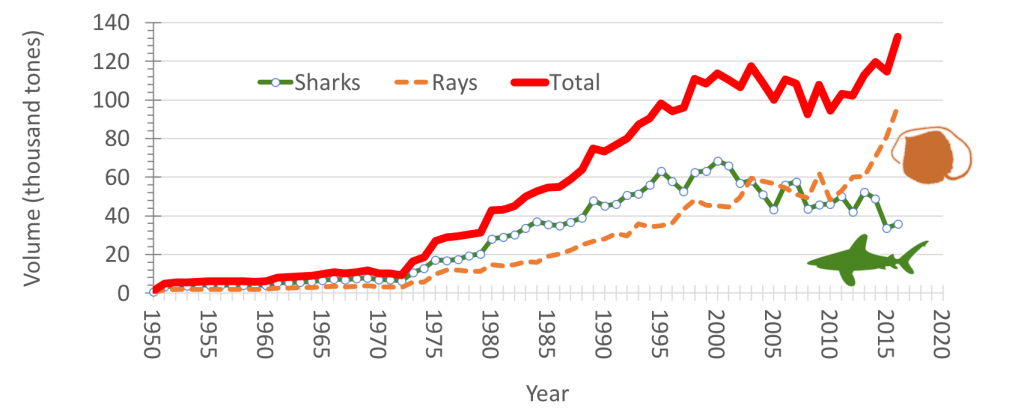

Indonesia is one of the world’s major fishing countries, consisting of approximately two-thirds ocean; it is also the world’s largest producer of sharks and rays (Figure 1). Sharks and rays are mostly caught as bycatch in other fisheries, but their economic value cannot be underappreciated. Even as bycatch, sharks and rays are valuable and marketable. In some places, a shift from bycatch to target catch has been observed.

Figure 1: Shark and ray landing in Indonesia 1950-2016 (Credit: A. P. Prasetyo; Source: DGCF-MMAF, 2018; FAO, 2018).

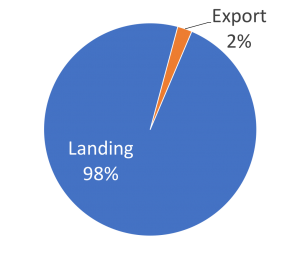

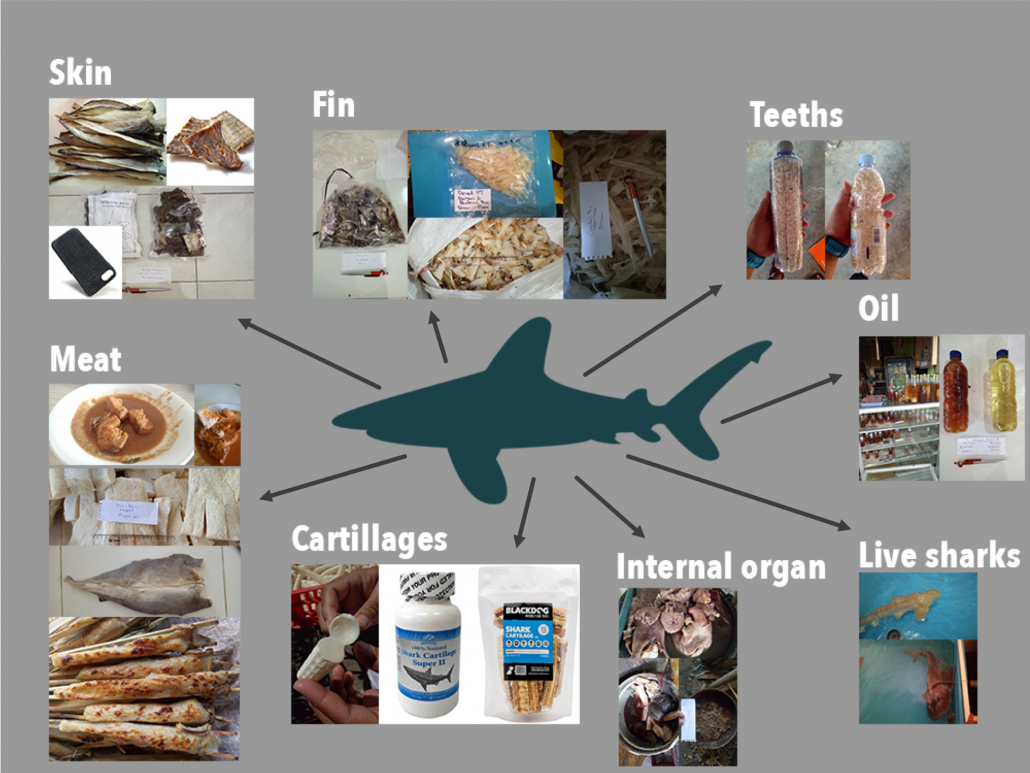

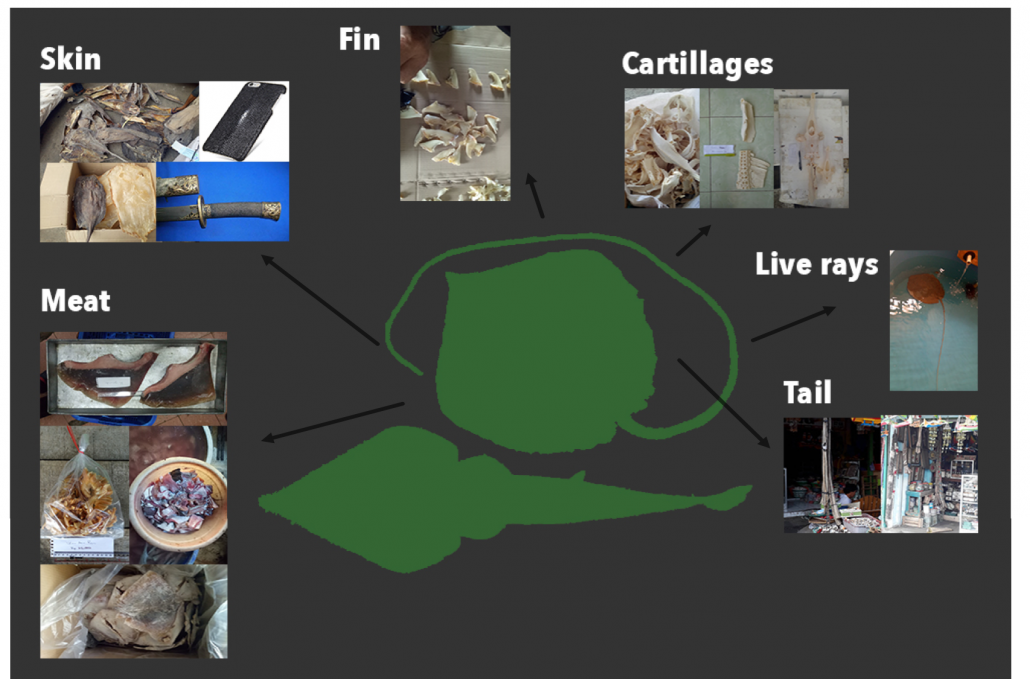

While fins are notoriously the most prized product derived from sharks and rays, every part of the animal is valued in Indonesia, including the meat, skin, cartilage, liver oil and offal. Products are processed in several ways and produced into a variety of products, such as hisit (shredded collagen fibres of fin), peeled fin, shark steak, salted meat, fish ball, squalene oil, cartilage powder, dog treats, belts, samurai sword handles and other accessories. Many of these non-fin products are used domestically. In 2016, shark and ray landings amounted to 132,746 tonnes while only 3,003 tonnes of shark products were recorded as exports (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Landing and export amounts of Indonesian sharks and rays in 2016 (AFQQI-MMAF, 2017)

Sharks and their cartilaginous relatives are subject to escalating global capture and trade. Their slow life history traits make them particularly vulnerable to overfishing and thus sharks are recognized as one of the world’s most threatened species groups. Aimed to curb trade-driven over-utilization and population declines, 30 shark and ray species have been listed on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and with the possibly of this increasing in the near future. This means international trade restrictions are applied, such that contracting countries to CITES are required to ensure trade is sustainable, without impacting wild populations.

However, in practice, export restrictions present a challenge for the authorities to ensure compliance with such international trade measures. This is particularly the case in Indonesia, considering its large volumes of products, diverse species and processed products, and many fishing and trading ports. Many products are highly processed, which subsequently loses key visual identification characteristics, making monitoring and implementation very challenging (Figure 3 & 4).

Figure 3: Shark derived products. (Source: A. P. Prasetyo/MMAF/Seafdec)

Figure 4: Ray derived products. (Source: A.P. Prasetyo/MMAF/Seafdec)

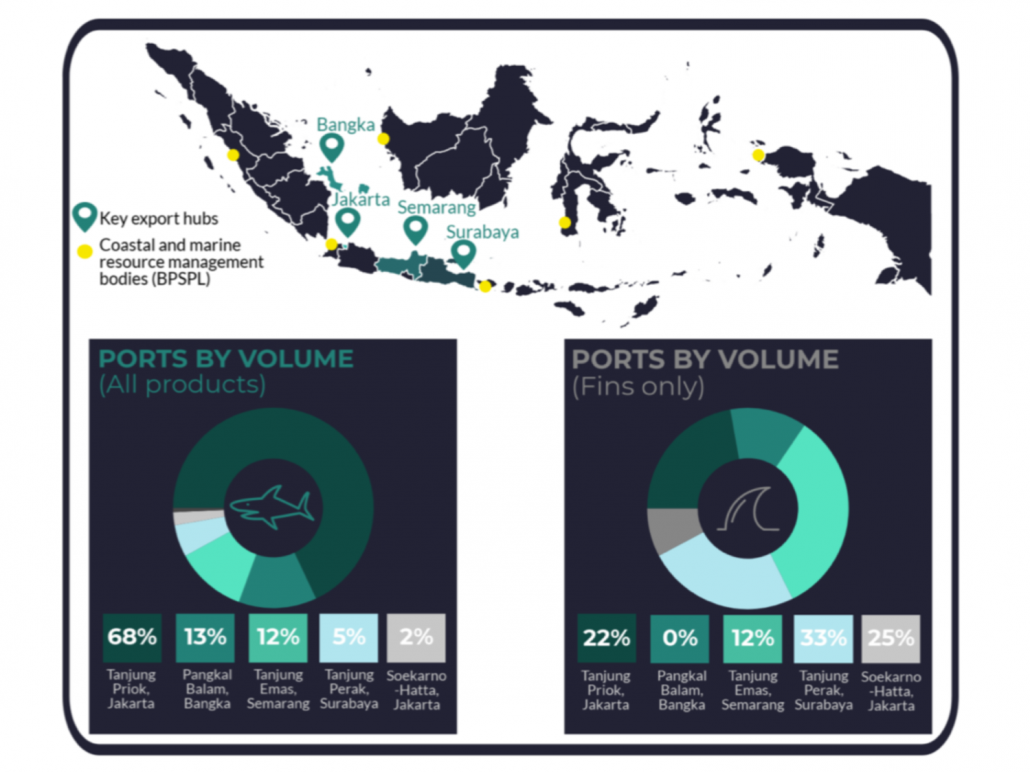

In Indonesia, the Coastal and Marine Resources Management Body (CMRMB, locally called “Balai/Loka Pengelolaan Sumberdaya Pesisir dan Laut”), is the Governmental technical unit tasked with shark and ray trade monitoring. There are 6 CMRMB offices located across Indonesia, with 17 regional operating units (Figure 5). Staff at these units are responsible for issuing trade recommendation letters, which authorizes shipments for transportation (domestically and internationally). This is a difficult job and requires high volumes of fisheries products to be handled, with the necessity of rapid species identification to ensure that CITES-listed species are not illegally and unsustainably traded.

Figure 5: Summary of shark and ray trade handled by CMRMB (Muttaqin et.al., 2018).

Between 2014 and 2017, the Serang CMRMB unit in Java successfully stopped, predominately through visual identification, approximately 250,000 individuals of 4 CITES-listed species: oceanic white-tip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus), hammerhead shark (Sphyrna sp.), thresher shark (Alopias sp.) and silky shark (C. falciformis).

A key challenge is that for many of these products, it is impossible to distinguish species by visual identification alone. CMRMB does not currently have molecular facilities to aid species identification, but since 2015 they have contracted other organizations to conduct genetic investigations to support CITES implementation. However, genetic testing is both time-consuming and financially unfeasible for regular use. It takes 3+ weeks to receive results and costs £110 per sample. Some CMRMB offices are located far from laboratory facilities and since the exporters are pushed to ship their cargo as quickly as possible, these time scales are not compatible with industry. The turnaround time for results also depends on the type of product. Some products need extra protocols to extract the DNA, such as dried fin, mixed hisit, dried skin, cartilage and oil.

Acknowledging this capacity gap, the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), in the UK, has been working with the Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (MMAF), the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the University of Salford since 2018, on a project funded by the Illegal Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund, to tackle the illegal and unsustainable shark trade in Indonesia. One component of the project is the development of a cost-effective molecular technique to rapidly identify shark species in trade, which can be practically implemented at export, and support CITES implementation and combatting of illegal trade.

At present, there are three types of genetic techniques used to identify shark and ray products: DNA Barcoding, Mini-DNA Barcoding and Species-specific PCR. DNA Barcoding involves sequencing a unique stretch of DNA for species identification. DNA Barcoding nearly always works on wet or dried, unprocessed fins, but often fails with dried, processed fins or other highly processed products that are likely to contain highly degraded DNA. For such samples, mini-DNA Barcoding is more suitable where two short DNA fragments are sequenced. A species-specific polymerase chain reaction (ss-PCR) is an approach that does not involve DNA sequencing and could reduce analysis cost. This approach amplifies DNA from target species and can identify 9 species of CITES-listed sharks. 9,200 shark fin by-products were tested by mini-DNA Barcoding in Hong Kong and revealed that CITES-listed sharks are still commonly being traded, such as scalloped and smooth hammerheads.

Over the next 3 years, this collaborative project will focus on applying, modifying and improving the existing molecular approaches in search of a cost-effective genetic approach that is suitable for Indonesia, and potentially other regions.

Andhika Prima Prasetyo is a researcher at the Center for Fisheries Research, Agency for Marine and Fisheries Research and Human Resources, Ministry for Marine Affairs and Fisheries – Republic of Indonesia. Currently, he is pursuing his PhD as an Industrial Sponsored PhD student in the School of Science, Engineering and Environment, at the University of Salford under the supervision of Professor Stefano Mariani, Dr Allan McDevitt and Dr Joanna Murray. A sincere thank you to Dr Adeline Seah, Ms Hollie Booth and Ms Nafeesa Esmail for their valuable review and contribution.