Posts

Complex interactions between commercial and noncommercial drivers of illegal trade for a threatened felid

New paper out, on 19.3.2021 by Arias et al., in Animal Conservation discusses the drivers of the Illegal Wildlife Trade in jaguars in Bolivia based on interviews with local communities.

Illegal trade and human‐wildlife conflict are two key drivers of biodiversity loss and are recognized as leading threats to large carnivores. Although human‐wildlife conflict involving jaguars (Panthera onca) has received significant attention in the past, less is known about traditional use or commercial trade in jaguar body parts, including their potential links with retaliatory killing. Understanding the drivers of jaguar killing, trade and consumption is necessary to develop appropriate jaguar conservation strategies, particularly as demand for jaguar products appears to be rising due to Chinese demand. We interviewed 1107 rural households in north‐western Bolivia, an area with an active history of human–jaguar conflict, which has also been at the epicentre of recent jaguar trade cases. We collected information on participants’ experiences with jaguars, their jaguar killing, trading and consuming behaviours and potential drivers of these behaviours. We found that the relationships between local people and jaguars are complex and are driven largely by traditional practices, opportunism, human–jaguar conflict and market incentives from foreign and domestic demand, in the absence of law awareness and enforcement. Addressing jaguar trade and building human–jaguar coexistence will require a multifaceted approach that considers the multiple drivers of jaguar killing, trade and consumption, from foreign and local demand to human–jaguar conflict.

Watch the video here (in English)

How do we Understand Illegal Wildlife Trade?

The term “wildlife trade” usually conjures up images of dead elephants, rhinoceros and tigers that are poached by organised criminal gangs for use in traditional Asian medicines, but there is far more to understanding wildlife trade.

A small number of charismatic species has been the narrow focus of most conservation efforts, funding, news and public attention. In reality, wildlife trade involves thousands of species and a wide range of products, from food to cosmetics to building materials. Even for a single species, this can involve very different products. For example, rhino horns are traded not only as medicines, but also as ornaments for carving. Unsurprisingly, these different species, products and situations involve different types of trade, including distinct roles for the harvesters, intermediaries (middlemen) and consumers involved.

Moreover, while wildlife trade is mostly portrayed as inherently illegal and nefarious, most wildlife trade is legal—including types of fishing, harvest of non-timber forest products, logging, and hunting for recreation and for meat. Even cases that may be ecological unsustainable are often legally permitted. In contrast, Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) specifically involves the harvest, trade and use of wildlife in ways that contravenes environmental regulations, such as protected area rules or the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

However, these types of nuances and diversity of contexts, products and actors are often overlooked, limiting our ability to design strong conservation projects. For example, the conservation lessons and policies designed to protect rhinoceros in Southern Africa may yield relatively few insights for people trying to protect parrots in Central Africa.

Our research group based at the Lancaster Environment Centre, works on a broad range of IWT issues, including the trade of wild ornamental orchids globally, edible frogs in Southeast Asia, aquarium fish in the Philippines, wildlife harvest within protected areas in Venezuela, and the lives of people arrested for IWT within Nepal’s prisons. Across this wide range of situations, we have struggled to identify ways of to systematically studying, understanding and discussing IWT.

In our recent paper in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, we propose some tools and terms that can help to address this challenge.

Summarised in this video, our framework helps researchers and practitioners to distinguish among different IWT species, products, actor roles and network structures, and can be applied in most contexts.

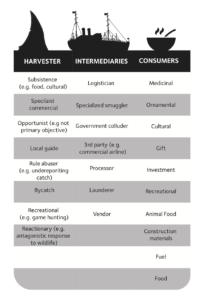

We distinguish among a huge diversity of actors potentially involved in IWT (Table 1) and argue that broad labels like “poacher”, “middleman”, and “criminal” fail to reflect the diverse realities and drivers of IWT. For example, IWT harvesters include local poor residents who occasionally, and opportunistically harvest wildlife to sell illegally as a supplementary livelihood. However, they also include people who have legal rights to harvest wildlife (e.g., from a timber concession), but abuse those rights by exceeding their legal quotas. Both cases represent IWT, and recognising these differences is essential to responding with tailored conservation interventions.

Research on the ground highlights that IWT is much more complex and diverse than is commonly recognised, and that we cannot base policies on lessons learned from single charismatic species or on popular myths about illegal trade. We need grounded research to specifically define products, characterise the people involved and understand the networks that link them, in order to create targeted interventions that are fair, realistic and effective. We hope that our framework will be tested and refined with a range of other contexts, and will help us to make comparisons, draw lessons and develop monitoring approaches across all IWT work.

Article edited by: Nafeesa Esmail

Understanding complexities of the world’s biggest shark and ray fishery

By: Hollie Booth, Sharks and Rays Advisor, South East Asia, Wildlife Conservation Society

Komodo National Park in western East Nusa Tenggara province, Indonesia, attracts tourists from all over the world to experience world-class scuba diving. Luscious reefs and tumultuous currents create a diverse, breath-taking environment, home to healthy populations of charismatic marine megafauna. Dive tourists are almost guaranteed to get up-close and personal with several shark and ray species, but it’s the 4m wide manta rays, soaring across the shallow, sandy banks of ‘manta point’, that are the biggest attraction. O’Malley et al., (2013) estimated tourists to spend over 10 million USD/year on diving with manta rays in Indonesia.

Approximately 500km east of Komodo National Park, in the fishing village of Lamakera, manta rays hold a completely different value. Lamakera is a relatively isolated, underdeveloped corner of the archipelago, where access to employment opportunities and infrastructure is limited, and with peak annual landings of up to 2,400 individuals in the early 2000’s, it is considered the world’s top manta ray hunting location. Small-scale manta ray fishing has operated in Lamakera for centuries, providing a source of sustenance and trade for the community, but growth and modernisation of fishing fleets coupled with a surge in demand for manta ray gills in Traditional Chinese Medicine markets has led to dramatic intensification of manta ray exploitation for commercial trade. Mantas are slow-growing and long-lived, making them highly vulnerable to overexploitation, and annual catch in Lamakera has been gradually declining since the early 2000’s, despite increases in fishing effort, indicating a population crash.

The stark contrast between these two sites within the same province in Indonesia illustrates the diversity of use and value of sharks and rays in Indonesia; the influential role globalisation and international markets play in shaping our relationships with nature; and the complexities and trade-offs involved in delivering conservation solutions. Recognising this, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) is working to support shark and ray conservation in Indonesia through a multi-faceted approach from policy, regulation and law enforcement to outreach and livelihood-focused interventions.

Specifically for manta rays, WCS assisted the Indonesian government to develop a ministerial decree to protect manta rays throughout the entire country in 2014, which has been followed by support for enforcement of this decree by investigating and arresting traders in illegal manta ray products, and dismantling illegal trade syndicates; working with partners to develop options for livelihood diversification in manta fishing communities; and monitoring changes in trade and exploitation to assess the impact of regulation and enforcement. Preliminary impact assessment results suggest the regulation is influencing manta ray exploitation rates in at least one site where socialisation and enforcement has been clear and consistent, but the nature and magnitude of the country-wide impact is not yet clear (Booth et al. 2016). Perhaps more importantly, this process is revealing valuable lessons in the challenges of implementing, monitoring and evaluating wildlife protection regulations in dynamic and complex contexts. In particular, there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach: effective shark and ray conservation requires multiple interventions, adapted to the motivations and interests of local groups and circumstances.

Moving forward, WCS is working with government and research partners to develop integrated data collection systems for understanding the magnitude of exploitation and trade of all shark and ray species throughout Indonesia. In partnership with the Oxford Martin Programme on the Illegal Wildlife Trade, as a new case study researchers will explore:

- What is the magnitude of illegal shark and ray trade in Indonesia, and how has illegal trade changed as a result of law enforcement?

- Who are the key consumers of shark and ray products, in Indonesia and internationally?

- What are consumer characteristics and motivations, and how can we design behaviour change interventions to encourage responsible consumption?

Research outputs will be used to inform the design, evaluation and adaptation of practical conservation measures to encourage responsible consumption of sharks and rays, which we hope will contribute to restoring healthy populations of sharks and rays, which can deliver both ecological and socioeconomic benefits for Indonesia.

See here for more information on WCS Indonesia and our other conservation programs.

Article edited by: Nafeesa Esmail

The power of supportive collaborative efforts, capacity building and local involvement

By: Elizabeth Davis, David O’Connor and Jenny Anne Glikman, Research Associates, San Diego Zoo Global

In 2014, San Diego Zoo Global (SDZG) began collaborating with Free The Bears, a number of universities and governments in SE Asia to address wildlife trade. The aim was to develop a framework that could be effectively and easily used by diverse organisations, regionally to gather data on the public knowledge, attitudes, behaviours, preferences, influences and consumption patterns of wildlife products. With a core set of questions, and the use of complementary methods (in-person surveys and semi-structured interviews), data collected from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos can be analysed together to begin to provide a better regional picture of the dynamics and drivers of wildlife trade consumption. Not only will this inform the development of demand change interventions, but this will also allow researchers to track outcomes of such efforts to gauge efficacy over time. There are numerous researchers and organizations gathering data across the region, but unfortunately the data is not necessarily sharable.

We began with preliminary surveys about bears and use of bear parts in northern Laos from Lao nationals, Western tourists, and Chinese tourists. The goal of these surveys was to understand perceptions of bears in northern Laos, as well as to understand what aspects of the questionnaire worked, and did not work, in a Southeast Asian context. Results thus far indicate that knowledge about the link between bear part usage and decline in bear populations is low among Lao people, but high among Chinese tourists visiting Laos. It is possible that this greater knowledge of use and impact on bear populations is what has caused Chinese tourists to cite their preferred bear bile type as synthetic, rather than from wild bears, though further investigation is needed.

Lessons learnt informed an improved and refined questionnaire which is currently being used in surveys in Cambodia, again on bears and bear parts. At the same time, semi-structured interviews also took place in Phnom Penh, resulting in qualitative data that will complement the results found in the quantitative survey. Preliminary results identify bear part use to be among middle to upper-middle status Cambodian individuals, particularly when an individual has a connection or affinity towards Chinese individuals. Bearskin was heavily cited as a product in use, but the lack of wildlife trafficking data for bearskin highlights the need to explore this further.

SDZG and Animals Asia is also surveying Traditional Medicine Practitioners in Vietnam to understand traditional medicine practice involving bear products, through mail-in surveys. Although a different methodology, these surveys complement the work performed in Cambodia and Laos.

In collaboration with Free The Bears, Animals Asia, TRAFFIC Vietnam and the Oxford Martin Programme on the Illegal Wildlife Trade (OMP-IWT), we will build on the work from Laos and Cambodia with public attitude surveys across Vietnam on bears and bear part usage, as well as on tiger part and saiga horn (ling yang, 羚羊) usage.

The OMP-IWT case study on bear bile in China aims to include core elements of the SDZG SE Asia bear surveys, working towards gaining a regional understanding. Greater refined mixed-methods research will be imperative for truly understanding the trends and patterns we isolate in IWT. The OMP-IWT is sure to be a dynamic research-to-action body, utilising complementary mixed-methods applications and catalysing collaborations.

Article edited by: Nafeesa Esmail