Hiding under the shell: not enough to protect the ploughshare tortoise

By: Angelo Ramy Mandimbihasina, Conservation Scientist, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust

A Malagasy proverb, “Sokatra ilatsaham-baratra, henoy izany ry hazon-damosiko” means “the tortoise is well protected inside their shell and even thunder will not affect them”. However, not all tortoises can protect themselves from harm. The ploughshare tortoise is one example.

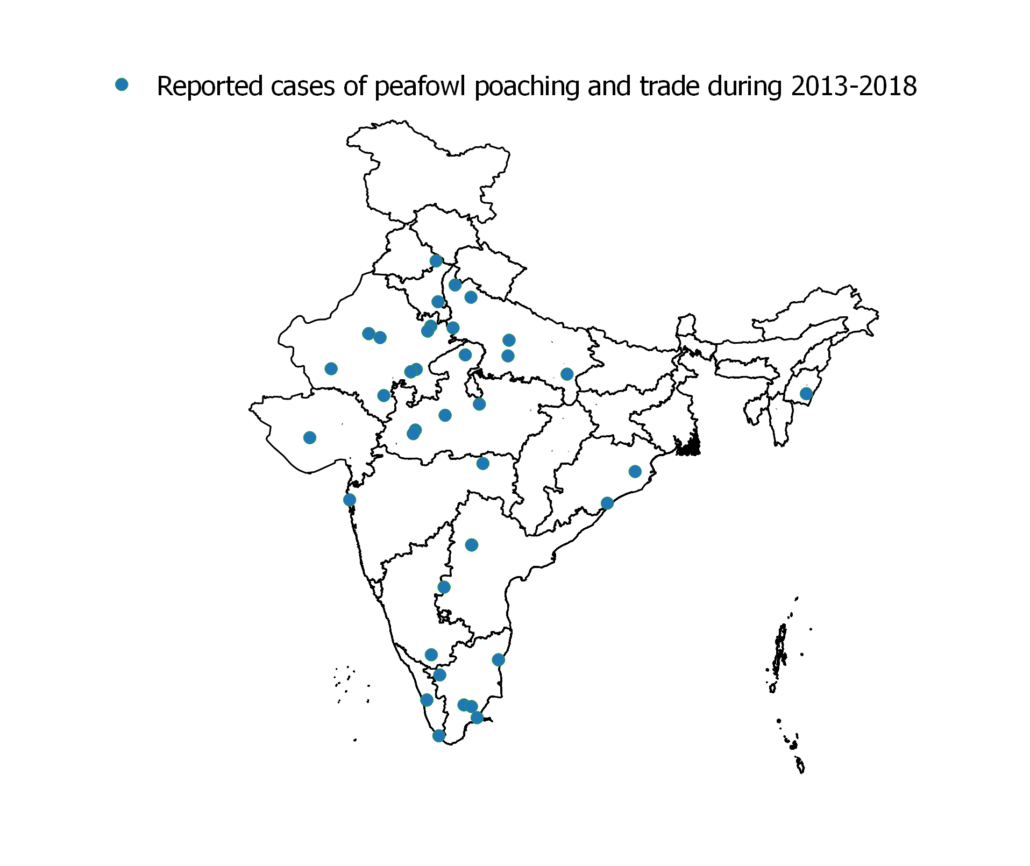

The ploughshare tortoise is terrestrial and endemic to an area of 160 km2 inside Baly Bay National Park, North-western Madagascar. This species (Astrochelys yniphora), has been classified by IUCN as Critically Endangered (CR), listed on Appendix 1 of CITES and protected locally by law – it is not permitted to harvest, captively rear or sell individuals. Its CR status is because the species’ natural population size is less than 1000 and continuously declining. Our recent research, a population study using distance sampling, in combination with seizure data, has concluded that the wild ploughshare tortoise population has declined from 1100 to close to 500 in about 10 years, because of poaching. These findings suggest that most of the trafficked animals supplying the illegal international wildlife trade originate from the wild, and are mainly destined for Southeast Asian countries.

Ploughshare tortoise. Photo credit: A. R. Mandimbihasina

Another driver of the drastic decline in ploughshare tortoise populations is the anthropogenic Allee effect. In other words, this species’ rarity is causing a high demand in destination countries, which raises prices locally. Rather than continuing to invest in farming, people living around the tortoise’s habitat may prefer to search for even just one tortoise, which has a greater value than their annual agricultural production, although this action can be very risky. Combined with other threats such as human-induced fires, ploughshare tortoise poaching may lead to the species’ extinction in the wild.

If we draw out the system of ploughshare tortoise poaching, we can distinguish the different actors involved. Locally, some people, known as “poachers”, search within the tortoise’s natural habitats for individuals. These poachers sell any harvested tortoises to intermediaries who are from either a nearby village or larger town and have connections enabling them to supply bigger customers or traders with the means to export tortoises.

In 2012, a conservation and management plan for the species was created, approved by the Ministry of Environment, Ecology and Forest, and adapted to fit the local situation. Captive breeding, scientific research, anti-poaching patrols as well as political advocacy have since been undertaken. Public awareness has also been used as a tool to explain to local villagers that they are losing their valuable biodiversity, which poses other ecological consequences to the ecosystem. An intact ecosystem is necessary to attract tourists and ultimately improve the region’s economy.

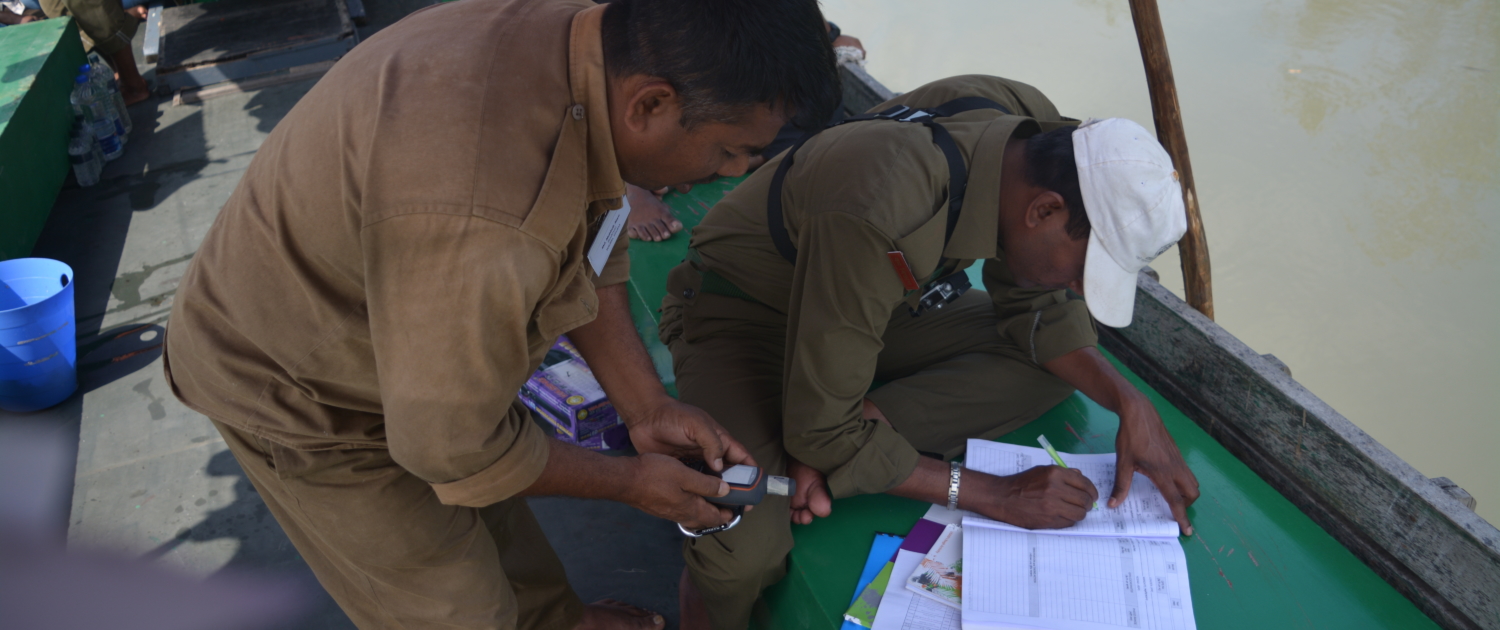

As an example, to reduce the threats, discourage poachers, and to better understand what is happening in the ecosystem, patrolling by local villagers, park rangers and military was initiated using smartphones to record patrol data. Data are uploaded into SMART, a package used to store, analyse and report results to support the planning of subsequent activities to reduce threats. This package can also be used to record any law enforcement actions taken and compile all results to evaluate the efficacy of the conservation interventions.

Ploughshare tortoise. Photo credit: A. R. Mandimbihasina

During village meetings and public awareness sessions, income-generating activities relating to farming or fishing practices were proposed to local villagers to increase their incomes and yields. The belief is that, if villagers are better off, poaching numbers will decrease because they will not want to continuously risk their lives.

To increase law enforcement and curb associated corruption, advocacy must be carried out locally, regionally and nationally, to convince people and the responsible government authorities at all levels to act to reduce this threat. Support is needed for an international campaign to reduce ploughshare tortoise demand and increase illegal wildlife trade control measures in airports and border crossings.

Article edited by: Nafeesa Esmail