Evaluating the design of behaviour change interventions

By: Alegria Olmedo, Senior Project Officer, WWF-Vietnam

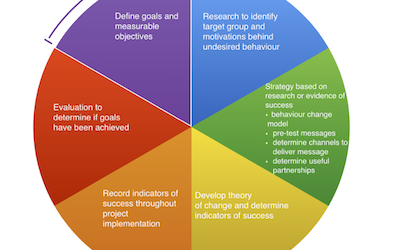

A recent research study evaluated nine behaviour change interventions launched in Vietnam in the decade leading up to 2015 to reduce the consumption of rhino horn. Using the grounded theory approach, interviews were carried out with representatives of nine organizations responsible for implementing interventions. A behaviour change intervention design wheel (Figure 1) was developed illustrating the key elements required for an intervention to achieve and demonstrate behaviour change. This wheel was created with elements of project design extracted from the behaviour change, conservation and business literatures and was later combined with themes that emerged from the conservations with interview respondents.

All interventions were assessed against this framework. Study findings illustrated a general lack of the use of each of these design elements.

Measurable Objectives:

Setting measurable objectives was possible for only one of the interventions due to a lack of baseline research.

Research and Target Audience:

Carrying out research prior to designing the interventions enables organizations to clearly identify a target audience and thoroughly explore the motivations driving consumption. However, only four out of nine interventions surveyed Vietnamese citizens to understand reasons for consumption and homed in on a particular demographic group for their intervention.

Evidence-based Messages, Behaviour Change Model and Theory of Change:

Only a third of the interventions delivered messages based on evidence that these might have the desired effect on the target audience. In addition, only two interventions were based on behaviour change models, indicating that in many cases assumptions had been made on how to achieve behaviour change. This is highlighted by the reliance on awareness raising, which has been widely used despite the lack of evidence that raising awareness of a particular subject leads to any change in behaviour.

Indicators of Success:

Although one intervention identified indicators of success, the implementing agent did not follow a theory of change or behaviour change model. Several other indicators were measured and treated as evidence of success, but many of these measure progress rather than success. These include: social media activity (to gauge interest and engagement), anecdotal information (particularly for pre-testing messages and reactions of individuals at workshops), number of people reached by messages via social media, texts sent by telephone companies, exposure on TV and workshop attendance (which does not indicate whether the people exposed to these messages were consumers, to begin with).

Evaluation:

Only two interventions produced baselines to evaluate the prevalence of rhino horn consumption and thus are the only interventions that could evaluate their impact.

Key challenges identified by practitioners implementing campaigns include:

- Lack of law enforcement – interviewees highlighted that behaviour change is part of a wider intervention landscape which includes law enforcement and legislative change; effective deterrents must be set in place to see a reduction in poaching, trading and consumption of illegal wildlife products.

- Cooperation – lack of cooperation has led to overlap and competition for territory of implementing agencies.

- Clarity of purpose – there are different ideas of what should be the aim of demand reduction work (awareness raising vs. behaviour change).

Whilst behaviour change may be a new tool to reduce demand for illegal wildlife products, lessons from other fields (i.e. public health, marketing and development) demonstrate there is no substitute for baselines, robust research and behaviour change models, which can be used to improve conservation interventions. Combining these valuable lessons with adequate support from governments is necessary to reduce demand for illegal wildlife products.

Article edited by: Nafeesa Esmail