How do we Understand Illegal Wildlife Trade?

The term “wildlife trade” usually conjures up images of dead elephants, rhinoceros and tigers that are poached by organised criminal gangs for use in traditional Asian medicines, but there is far more to understanding wildlife trade.

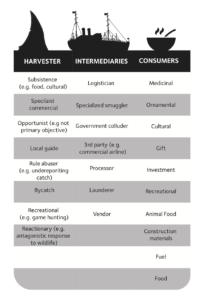

A small number of charismatic species has been the narrow focus of most conservation efforts, funding, news and public attention. In reality, wildlife trade involves thousands of species and a wide range of products, from food to cosmetics to building materials. Even for a single species, this can involve very different products. For example, rhino horns are traded not only as medicines, but also as ornaments for carving. Unsurprisingly, these different species, products and situations involve different types of trade, including distinct roles for the harvesters, intermediaries (middlemen) and consumers involved.

Moreover, while wildlife trade is mostly portrayed as inherently illegal and nefarious, most wildlife trade is legal—including types of fishing, harvest of non-timber forest products, logging, and hunting for recreation and for meat. Even cases that may be ecological unsustainable are often legally permitted. In contrast, Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) specifically involves the harvest, trade and use of wildlife in ways that contravenes environmental regulations, such as protected area rules or the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

However, these types of nuances and diversity of contexts, products and actors are often overlooked, limiting our ability to design strong conservation projects. For example, the conservation lessons and policies designed to protect rhinoceros in Southern Africa may yield relatively few insights for people trying to protect parrots in Central Africa.

Our research group based at the Lancaster Environment Centre, works on a broad range of IWT issues, including the trade of wild ornamental orchids globally, edible frogs in Southeast Asia, aquarium fish in the Philippines, wildlife harvest within protected areas in Venezuela, and the lives of people arrested for IWT within Nepal’s prisons. Across this wide range of situations, we have struggled to identify ways of to systematically studying, understanding and discussing IWT.

In our recent paper in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, we propose some tools and terms that can help to address this challenge.

Summarised in this video, our framework helps researchers and practitioners to distinguish among different IWT species, products, actor roles and network structures, and can be applied in most contexts.

We distinguish among a huge diversity of actors potentially involved in IWT (Table 1) and argue that broad labels like “poacher”, “middleman”, and “criminal” fail to reflect the diverse realities and drivers of IWT. For example, IWT harvesters include local poor residents who occasionally, and opportunistically harvest wildlife to sell illegally as a supplementary livelihood. However, they also include people who have legal rights to harvest wildlife (e.g., from a timber concession), but abuse those rights by exceeding their legal quotas. Both cases represent IWT, and recognising these differences is essential to responding with tailored conservation interventions.

Research on the ground highlights that IWT is much more complex and diverse than is commonly recognised, and that we cannot base policies on lessons learned from single charismatic species or on popular myths about illegal trade. We need grounded research to specifically define products, characterise the people involved and understand the networks that link them, in order to create targeted interventions that are fair, realistic and effective. We hope that our framework will be tested and refined with a range of other contexts, and will help us to make comparisons, draw lessons and develop monitoring approaches across all IWT work.

Article edited by: Nafeesa Esmail