On COVID-19, and rebalancing our relationship with nature

By Hollie Booth, Interdisciplinary Centre for Conservation Science, University of Oxford

Originally posted on the Interdisciplinary Centre for Conservation Science

2020 was supposed to be a super year for nature. Instead we got a pandemic.

Arguably, it is our strained relationship with nature that got us in to this mess. The evidence is fairly conclusive that the Sars-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 first made its way in to a human vector in a wet market in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. The original animal reservoir for the virus was probably bats. Available evidence suggests the virus first passed from bats to an unconfirmed intermediary host (maybe pangolins) and then from the intermediary to humans (Fig. 1), probably because someone ate the intermediary host.

Fig. 1. A simplified schematic of how the socio-ecological system of food production lead to COVID-19 in humans

So, what does this mean for our relationship with nature?

It reminds us how intertwined we are with nature, and how the choices we make about our food systems and broader human-nature relations can have rippling global impacts. COVID-19 evolved in the socio-ecological system of food production in China, which has undoubtedly been influenced by global market forces. It is a co-product of relentless human innovation for consumption and trade, and nature’s relentless capacity for adaption and evolution.

It reminds us that nature is not caring, kind and simply here for our benefit. In certain socio-ecological systems, nature has the capacity to be terrifying and destructive to humans, just as we can reap destruction on nature.

It reminds us how dependent we are on a habitable planet, and that the current globalised economic system is not de-coupled from nature and immutable to its impacts. Rather, our relationship with nature needs to be re-balanced. Some argue that this is sufficient justification for increasing separation of humans and nature, for example through closing wildlife markets in their entirety. Yet this fails to sufficiently acknowledge the complexity and precariousness of human-nature relations. Humans depends on wildlife for food security and livelihoods, just as some species depend, in part, on human use for their survival. This creates a false dichotomy and decoupling of ‘natural’ and ‘human’ systems, yet the two do not operate in isolation, and we are often required to trade one off against the other. As such, stopping use of wildlife would have negative impacts for nature and people. For example:

- It will impact the food and livelihood security of millions of people who depend on wildlife, as well as undermining their rights and culture;

- It may increase habitat destruction and climate change, through requiring expansion of animal agriculture to meet the resulting food gap, and removing incentives for wildlife conservation.

In turn, this may exacerbate risks to human health due to increased food insecurity, increased interfaces between animal agriculture and undisturbed ecosystems (more of step 1), and potential increases in illegal and unregulated wildlife trade (more of step 2).

Fig. 2. The factors that increase the risk of zoonoses are complex and inter-twined, changing one aspect of our human-nature relationship will inevitably impact another. Source: UNEP.

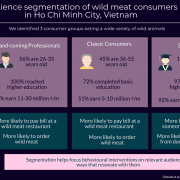

Whether to increase regulation of wildlife markets in response to COVID-19 is an open question and requires examining the likely impact of different policies on public health, biodiversity, animal welfare and broader socio-economic issues. Moreover, it requires a critical analysis of the proximate vs. ultimate causes of zoonotic disease emergence. Other factors such as urbanization, population density, socio-economic status and agriculture play major significant roles in zoonotic disease emergence. Interestingly, while many are quick to point the finger at China’s eating habits in this instance, the majority of human infectious diseases emerged for the first time in northerly latitudes, with a hotspot in Europe. As such, regulation of wildlife markets is not a panacea for preventing emergence of zoonoses, it is one piece in the complex puzzle of our human-nature relationship (Fig. 2).

It also reminds us that while nature can be cruel, it can also provide solace during times of distress. With an estimated 2.9 billion people in some form of lockdown, we may not be able to interact with people, but at least we can find solitude in nature (at least we can in the UK, during our ‘one exercise per day’ allowance), and appreciate the simple things in life (Fig. 3). This may provide an opportunity to reconnect with our values, reflect on the sustainability of our choices, and transition towards new ways to live, work and organise the global economy.

Fig. 3. Reconnecting with nature can help us to cope with social isolation, and reflect on what’s important

Our relationship with nature got us in to this mess, but it can also get us out of it. On an individual level, for those of us who are lucky enough to be fit and healthy, we can disconnect from the hubbub of our work lives and reconnect with ourselves and nature. On a societal level, we can learn lessons from this tragedy, to reset our relationship with nature, and find creative ways to live more happy and sustainable lives, which can benefit public health, nature and our ever inter-twined socio-ecological system.

[With thanks to Dan Challender, Munib Kahnyari and E.J. Milner-Gulland for their helpful inputs to an earlier draft]

OMP-WT

OMP-WT

OMP-WT

OMP-WT Alegria Olmedo

Alegria Olmedo OMP-WT

OMP-WT

OMP-WT

OMP-WT OMP-WT

OMP-WT