Urban bushmeat trade: the restaurant’s recipe

By: Sarah Gluszek, Conservation Criminologist, Michigan State University* @SarahGluszek

Collaborators: Julie Viollaz (Conservation Criminologist, Michigan State University @julie_viollaz), Robert Mwinyihali (Urban Bushmeat Coordinator, WCS Central Africa @rmwinyihali), Michelle Wieland (Socio-Economic Advisor, WCS Africa @Pygmykingfisher), Meredith L. Gore (Associate Professor, Michigan State University @meredithgore)

Globally, cities are growing exponentially; there are currently more people living in urban centres than in rural areas. Urbanisation is globally associated with unprecedented change to both wild and human-dominated landscapes. For example, the impacts of urbanisation and urban populations on bushmeat consumption are not fully understood, although the scope and scale brings new conservation challenges as megacity appetite for wild foods (not to mention charcoal) remains. Specifically, the illegal and unsustainable urban bushmeat trade poses a threat for conservation and sustainable development. Although bushmeat consumption by urbanites is not new, little is known about the supply chains enabling illegal trade. To date, research has prioritised quantifying bushmeat availability and prices over exploring urban demand and the motivations underlying the sourcing of bushmeat.

By 2030 the number of Africa’s megacities (cities with at least 10 million residents) – and its number of secondary cities (those with populations up to 3 million) – is expected to double. Central Africa is unique in that it is home to Congo Basin’s immense forest, hosting a high sociocultural diversity and is interspersed with large urban populations living in cities like Brazzaville (Republic of Congo) and Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo). Studies on the bushmeat trade in Central African cities have also mainly focused on consumers and households. Yet, little is known about a key player in Africa’s urban bushmeat markets – restaurants. Further engagement with the restaurant community to understand the drivers and consequences of urban bushmeat trade could help increase benefits for conservation and sustainable development. To this end, our team at Michigan State University and the Wildlife Conservation Society conducted a conservation criminology-based study of the urban bushmeat trade from the restaurateur perspective in the Republic of Congo and Democratic Republic of Congo.

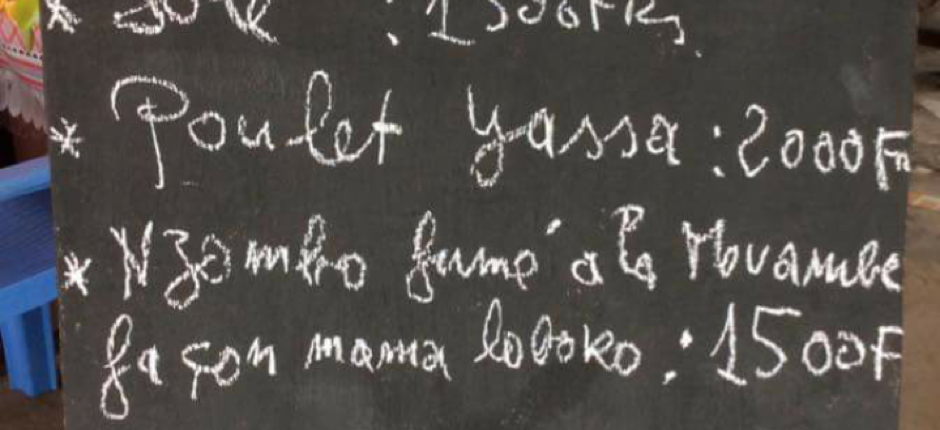

Typical menu board seen outside of restaurants selling bushmeat in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. Credit: L Escouflaire, WCS

Conservation criminology is an interdisciplinary approach integrating natural resource management, criminology, and the risk and decision sciences. It can be used to build policy-relevant science about environmental risks like that of illegal and unsustainable bushmeat trading in urban centres. Using this for our restaurant work, we: 1) identified the range of protected and endangered species traded for bushmeat, 2) applied crime prevention techniques to better understand trade dynamics, and 3) ascertained restaurateurs’ perceptions of the trade and how sourcing decisions were made. Six focus groups were held with restaurateurs in Kinshasa and Brazzaville in November and December 2017. Each focus group consisted of representatives from one of the three tiers of restaurant levels (i.e., upper, mid- and lower-priced). With each focus group, we led participants through a discussion identifying which bushmeat species were “hot products” in the urban trade and their connections with other supply chain actors in the trade.

Using the VIVA hot product analysis, we found monkeys were bushmeat “hot products” in upper- and lower-priced restaurants and collectively across all restaurant tiers in both cities (exampled in Figure 1). This group included monkey species protected by national and international laws, and vulnerable to extinction as classified by the IUCN Red List. Although not originally included in the study by researchers, participants identified elephant and hippopotamus meat as being occasionally traded in Kinshasa and Brazzaville. Linkages between restaurateurs and supply chain actors in the urban bushmeat trade were mapped and collectively analysed.

Figure 1: Monkeys, identified as “hot products” by the VIVA analysis, sold overtly in Kinshasa street markets. As pictured, they can be smoked, making it difficult to identify species and whether they are endangered or protected by law. Credit: S Gluszek, MSU/WCS

Mid-priced restaurants had the strongest networks, being the most connected with actors along different points in the supply chain. Lower-priced restaurants had smaller networks and were more dependent on local city markets for their bushmeat sourcing. Meanwhile, upper-priced restaurants were most reliant on supply chain actors operating as middlemen between them and bushmeat suppliers at the source.

Cities act as both transit routes and destinations for the urban bushmeat trade. This exploratory study suggests that certain types of bushmeat, such as endangered monkey species, are more at risk of extinction due to a combination of supply and demand side factors; they have threatened population numbers and are additionally vulnerable as ‘hot products’ in the urban bushmeat trade. Moving forward, a more comprehensive “hot product” analysis could be applied such as CRAVED/CRAAVED. With a better understanding of the relationships between restaurants and other supply chain actors in the trade, we can be better apply nuanced conservation responses, such as situational crime prevention techniques to prevent illegal wildlife trade opportunities. This study highlights the potential to involve the restaurant and catering industry, as well as local urban community members, with the recognition that they can play a role in combating urban wildlife crime. Not only in terms of law enforcement, but also by acting as agents of change with their purchasing power and menu selections. Among our study participants, restaurateurs from Kinshasa and Brazzaville were generally willing to participate and work towards creating a more sustainable trade to protect their livelihoods, a positive outcome paving the way for future collaborations and opportunities.

*current affiliation: Wildlife Trade Technical Specialist, Fauna & Flora International

Article edited by: Nafeesa Esmail

Tim Boekhout van Solinge

Tim Boekhout van Solinge Pooja Pawar

Pooja Pawar