Understanding the role of ivory traders by leaving the ivory tower: the value of ethnography

By: Kristof Titeca, Assistant Professor, Institute of Development Policy, University of Antwerp @KristofTiteca

It has been widely shown how the illegal ivory trade has increased enormously in the last decade. There is particular interest in the export of raw ivory from sub-Saharan Africa towards East and South-East Asia. Particularly the Elephant Trade Information System (ETIS), the global database of reported seizures of illegal ivory has led to a number of excellent analyses. There equally has been a range of interesting studies relying on insights from law enforcement officers, which particularly highlight how corruption is driving illegal trade.

Yet, while the illegal ivory trade has been analysed from a number of perspectives, one actor’s perspective is largely missing from these analyses; the illegal ivory trader himself. On the one hand, this is understandable: approaching ivory traders brings a range of methodological difficulties. Given their illegal nature, it is difficult to find and/or approach them. On the other hand, doing so could be useful, in order to further unpack and understand the illegal ivory trade(rs). For example, the literature on poaching gives fascinating insights into unpacking the homogenous understanding of what constitutes a poacher, or why people engage in poaching. This literature for example shows the difference between subsistence and commercial poachers; whereas the first group typically targets small game and hunts to meet food needs, the second group targets commercially more viable game.

These insights only were possible through in-depth research among the poachers, i.e. the actors themselves. A similar analysis – what I provocatively call ‘leaving the ivory tower’, towards the traders – could help to give better insights, particularly in identifying the ways in which ivory goes from poaching hotspots to exit-points out of Africa.

Insights from the wider field of criminology, anthropology, sociology and other disciplines have shown the possibility of conducting research on illegal activities, including gangs, rebel groups or illegal traders. What most of these disciplines have in common is their method of data collection; ethnography, and/or long-term engagement in particular areas, and with particular groups. This often involves sheer luck – a lot of the fascinating research on gang violence, for example, involved chance introductions, eventually resulting in long-term research. This was the case for my own research on illegal ivory traders in Uganda (and to a lesser extent in the Democratic Republic of Congo); rather than resulting from a predetermined plan and introduction, it was ongoing research on illegal cross-border trade, which led to introduction to illegal ivory traders – facilitated by the fact that many of these traders themselves started trading in illegal ivory between 2008 and 2009. This ongoing research is a (humble) attempt to contribute to the debate on illegal ivory trade, more particularly in the ways in which raw ivory is moved towards exit points, and a further unpacking of the various categories of ivory traders.

By following a number of individual illegal ivory traders between 2012 and 2017 in Uganda, my research aimed to further unpack the homogenous account of the ‘trader’ – a central, but much neglected actor in the studies on illegal ivory trade, and illegal wildlife trade in general. My research came up with the following findings (the first article of which has been published in the British Journal of Criminology).

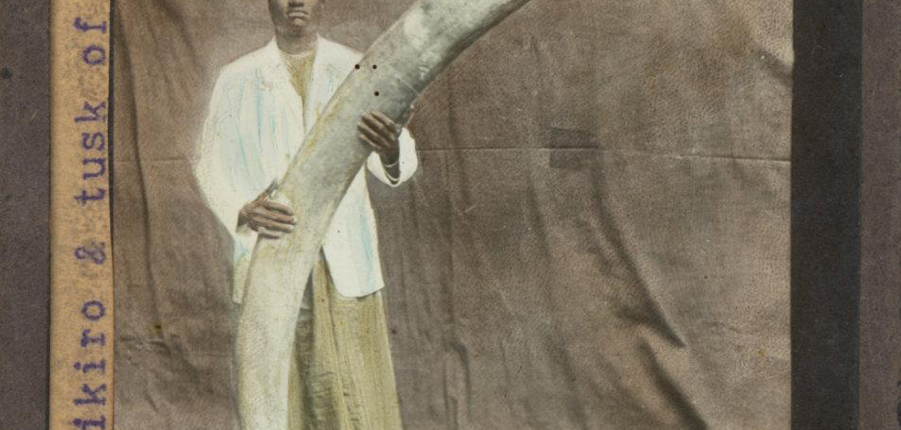

Ivory trader. Photo credit: HIPUganda (History in Progress Uganda)

First, (and similar to the findings from research among poachers), there are severe power differences among ivory smugglers. These differences are largely related to connections with government officials; the better the connections with high-level government officials, the more power the trader has. This gives a range of advantages to the traders, including access to hotspots such as the airport, more diversified sources of ivory, better protection against confiscations, and so on. Concretely, some traders limit their activities to their home turf, where they know the customs officials, transporters, police agents, and so on. The Uganda-Congo border area is an example of one of these nodes; historically, this border region has been a node for smuggling, bringing together a wide range of traders and commodities. The nature of these commodities depends on market and taxation dynamics; some years, fuel and cigarettes are popular, other years second hand clothes have been particularly interesting. From around 2008, ivory became part of these trading dynamics, which largely came from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Yet, most of these traders didn’t have the power and connections to directly sell this ivory in the capital Kampala, or take it through the airport. Instead, they sold it to more powerful traders, who did have power in the Kampala ‘node’.

Second, building on the age-old social science debate on the tension between structure and agency, a focus on the traders allows one to understand the way in which ivory traders navigate particular structural circumstances. In a forthcoming article in International Affairs, I analyse the ways in which traders handle changing circumstances, such as increased confiscations, stronger punishments, price fluctuations, and so on. In doing so, I show how traders shift between various commodities, depending on these circumstances (from ivory to drugs), or leave the trade altogether. Also here, power differences explain the way in which these difficulties are handled; given the increased ivory confiscations, only elite actors remain in the trade. In other words, the more the state clamped down on ivory trade, the more connections with state officials were necessary to survive in this trade.

Third, transnational and local actors mutually depend on each other; transnational actors such as Chinese traders do not dominate the trade, but are largely dependent on local actors, who are necessary for transport, supply, etc. Many transnational actors therefore depend on historically embedded trading networks. Concretely, much of the ivory coming into the Uganda-Congo border region comes from a wide variety of regions and traders, in a largely uncoordinated manner. It is the traders in this node who are able to smuggle the ivory across the border, and store it for the transnational traders, which are largely dependent on the local traders’ supply routes.

Article edited by: Nafeesa Esmail

Meryl Theng

Meryl Theng Neil C. D'Cruze

Neil C. D'Cruze